|

| Brace yourself Microsoft. It's your turn now. |

With a new Windows version coming out, 8 is of course dominating the tech blogs. I haven’t looked much myself, but I’m assuming there’s gushing praise from Microsoft fanboys and scathing remarks from the hardcore Mac and Linux fans. I really have no appetite for a string of blog posts on one product myself, but having had a look at Windows 8, there’s now one extra thing that’s grabbed my attention other than the Windows Store, and that’s the Metro Interface (it’s now called the “Modern UI” due to a copyright row, but everyone’s still calling it Metro). I promise to move on to something else next time.

This new interface has grabbed a lot of attention, and not all of it’s good. Microsoft’s incentive is to make Windows 8 more friendly to tablet users where they desperately want to compete with Apple and Android, but they risk alienating their desktop customers. I have now tried out their interface and I can confirm it’s a right pain in the bum to operate with a mouse compared to the Start menu it replaced. I can see this being good for touchscreens, but there’s no sign touchscreens are going to replace keyboard, mouse and monitor in the office. Usability is a major issue for mass consumer software, and from the sound of some commentators you’d think this was Windows suicide.

Well, the good news for Microsoft is that there’s a favourable precedent here. Two years ago Canonical did something similar with Ubuntu 11.04 aka Natty Narwhal and its controversial Unity interface. There were a number of factors behind this decision, touchscreen-friendliness being just one of them, but there was a similar scornful reception from the Ubuntu faithful as there is from the Microsoft faithful now. I was just as sceptical about Unity then as I am about Metro now. In fact, after trying out Unity on my test partition, I decided to upgrade to Ubuntu 11.04 – but only once I knew how to force it back to the old interface.

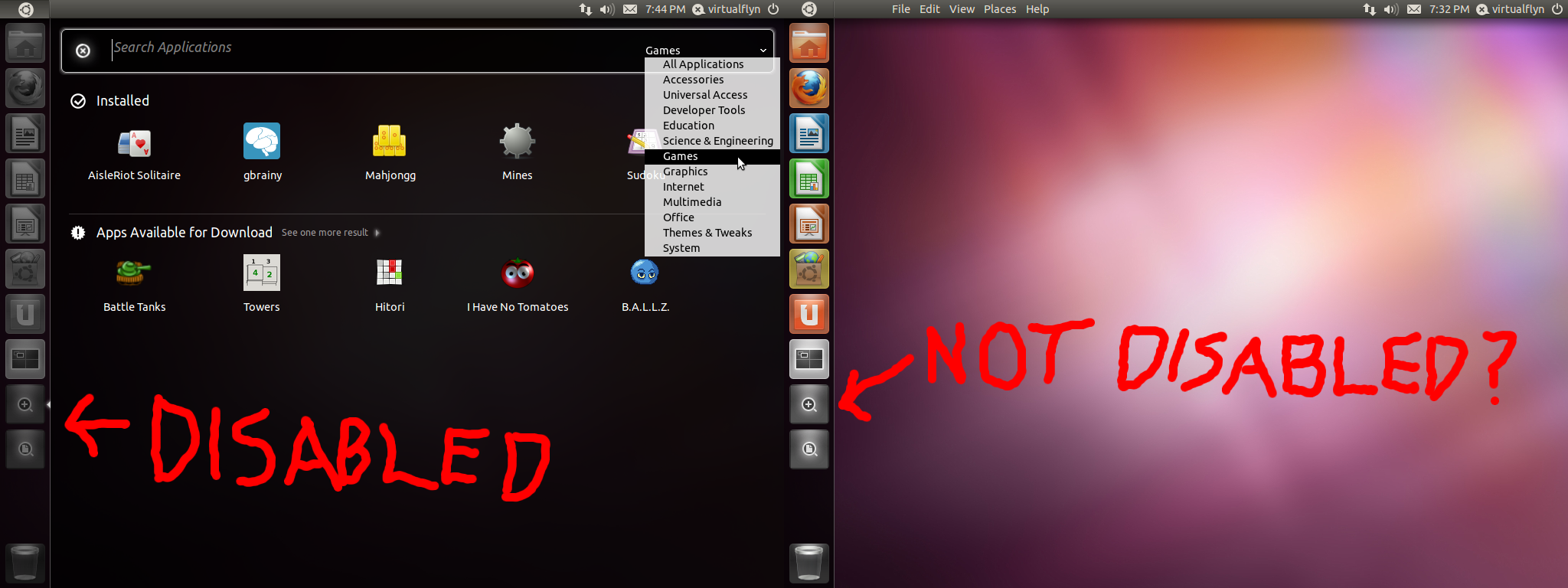

And here’s the good news. I kept Unity on my laptop and netbook (Unity was partly designed as a space-optimised OS for small-screen netbooks), and after while started to understand where it was coming from. The Dash interface was a nightmare to use as a replacement to the Launcher (the Linux equivalent of the Start Menu), requiring numerous extra clicks to launch a program. But once you put all your key programs in the sidebar (which, realistically, is unlikely to be much more than the web browser, word processor and spreadsheet for most people), that’s not a big issue. I found the buttons at the side are a good way of keeping track of different windows belonging to the same program (very similar to the Windows 7 taskbar), and when used in conjunction with the new-look virtual desktops it becomes a powerful way of organising all your windows. There were a couple of feature I felt were more trouble than they were worth on desktops (overlay scrollbar and Global menu), but were easily disabled. When the next release came out six months later and the Unity interface had been refined a bit, I finally make the leap. And this was the experience of a lot of users.

And this is an important lesson in usability for Microsoft and everyone else: it can take months or even years to know if an interface change is a success. I’ve said previously that usability testing is hard because developers and testers, by definition, don’t know what it’s like to be a novice on a computer. One solution is to bring in non-technical people for usability tests, but this example shows a limitation: how can a few days or even a few weeks testing tell you what users think in six months’ time? We know from Ubuntu that it can take months or years for a change to gain acceptance from your users. Canonical and Microsoft both chose to the sceptics, then go ahead anyway and hope for the best. Canonical got away with for Unity, and that’s where there’s hope for Microsoft and Metro.

But it would be foolish to use Unity as proof that it’ll all be fine in the end. There’s a fine line between introducing unpopular changes that gain acceptance over time and imposing unpopular changes that stay unpopular. Facebook’s timeline looks set to be the latter. The Microsoft Office ribbon is at best a “Marmite change”, where you either love it or hate it. Unity wasn’t a complete success, because some users switched to Linux Mint (an Ubuntu fork that, amongst other things, stuck with the only Windows XP-like interface). In any case, there’s only so far you can go using Linux as a precedent for Microsoft. Linux users are a different demographic group to Windows users, generally more tech-savvy (so more likely to customise their favourite OS from the default setting but also more likely to switch distros if they get too annoyed), and generally different expectations. There’s no knowing if a change accepted by Linux users will also be accepted by Windows users.

If it was up to me, I would have made the new “Metro” interface the default for tablets and the old interface – including Start button – the default for laptops and desktops. Nothing particularly against this interface; just that Unity struck me as a good all-purpose balance between desktops, notebooks, netbooks and tablets, whilst the new Windows 8 screen strikes me as heavily optimised toward tablets. Or, at the very least, they should make it easy to switch back to the old interface with a few clicks. I know that maintaining two different interfaces is extra work (Linux users who stray from the default settings too much will find themselves running into bugs quickly), but – come on, it’s Windows, the highest-selling piece of software in the world, Microsoft can afford to do this.

But it’s unlikely this change of interface will be a Windows killer. Microsoft has many things to worry about – lack of Windows 8 app, a minor share in the smartphone market, open-source competitors getting better, the prospect of Android making the leap from tablet to desktop – but the Ubuntu experience shows that outrage over user experience tends to be a short-term thing. The real test will behow well Microsoft adapts to the changes to the IT market in the last decade – and it will take more than a change to the start page to make or break Windows.

No comments:

Post a Comment